George Fullerton (left) testing a Stratocaster in the Fender factory, sometime in the mid-to-late 1950s. Photo courtesy of Richard Smith.

Many places deserve to be called the birthplace of rock ’n’ roll. Memphis often gets the nod because that’s where Sam Phillips of Sun Records recorded Elvis Presley belting out an impromptu, uptempo cover of “That’s All Right” in 1954. Cleveland makes the list since it’s the place where, in 1951, a local disc jockey named Alan Freed coined the genre’s name. Chicago’s claim precedes Cleveland’s by several years; in 1948, McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters, took the tiny stage of a neighborhood tavern called Club Zanzibar, pulled up a chair, and played his hollow-body electric guitar so loud, the sounds emanating from his small amplifier crashed upon the sweaty crowd in waves of soul-stirring distortion.

“The Fender Esquire was derided by competitors as a toilet seat with strings.”

Those would all be good choices, but for author Ian Port, whose new book, The Birth of Loud, has just been published by Scribner, the birthplace of rock ’n’ roll could also be the former farming community of Fullerton in Orange County, California. That’s where an electronics autodidact named Clarence Leonidas “Leo” Fender founded a radio repair shop in 1938. By 1943, Fender and a friend named Clayton “Doc” Kaufman, who was Fender’s business partner in those days, had taken a solid plank of oak, painted it glossy black, attached a pickup at one end, and strung its length with steel strings (see photo here).

Leo Fender amid numerous G&L guitars, a company he ran with George Fullerton years after he sold Fender. Photo via the Rock Hall Library and Archive.

This “radio shop guitar,” as Port calls it in his book, was very similar to the tabletop “steel” guitars that Fender and Kaufman were manufacturing for the country-western swing bands playing the honky-tonks and dance halls of Southern California, except this one could be hung from a strap around the neck and played while standing up, just like a traditional “Spanish” guitar, as regular guitars were called in those days. As Port tells it in The Birth of Loud, Fender didn’t believe his and Kaufman’s prototype had been built well enough to sell to anyone, but he regularly rented it to “Fullerton’s cowboy pickers,” who would “roar through that proud little downtown on their motorcycles, pull up to Leo’s shop three doors down from the main intersection, breeze past the shelves of records and radios for sale, and ask for that black guitar. There was only one.”

The romance between country musicians and solid-body electric guitars continued in 1947, when a country-music star named Merle Travis asked a steel-guitar competitor of Leo Fender’s named Paul Bigsby to make him a Spanish style, solid-body electric. Bigsby’s Merle Travis guitar, delivered in 1948, would prove highly influential, particularly to Leo Fender, but it wasn’t until the rock ’n’ roll musicians of the 1950s and ’60s embraced solid-body electrics that guitar players were transformed into bona-fide guitar heroes. In the process, they elevated their genre to heights no one in postwar Southern California—or Chicago, Cleveland, or Memphis, for that matter—could have possibly imagined.

Les Paul with a few of his clunker guitars. Photo via the Rock Hall Library and Archive.

The Birth of Loud chronicles this evolution, mostly via the short friendship and longer rivalry between Leo Fender and jazz guitarist Lester Polsfuss, better known as Les Paul, after whom the venerable Gibson Guitar Company named its first solid-body electric guitar in 1952. Port tells us who did what first, who stole which ideas from whom, and explains why live performers considered the solid-body electric guitar to be such an essential improvement over the hollow-body electric guitars that had come first (Muddy Waters-style distortion was one thing, but hollow-body electrics were prone to producing ear-piercing shrieks and screeches of feedback).

Port’s passion for his subject grew from his love of music and, in particular, guitars. “I’ve been a guitar player pretty much my whole life,” Port told me when we spoke over the phone recently. “I think I got my first electric guitar, a Peavey Predator, when I was 10 years old. It was a beginner model, a Strat copy, but a really nice guitar. I still pick it up and play it sometimes.”

The original color of the 1954 Fender Stratocaster was a three-toned sunburst. Photo via Gbase.

“Strat,” as in “Stratocaster,” a model introduced by the Fender Electric Instrument Company in 1954. “Strat,” as in the guitar Buddy Holly purchased in Lubbock, Texas, in the spring of 1955, and subsequently took with him when he conquered the UK in 1958. On that tour, Holly’s trio, the Crickets, were booked on a television variety show called “Val Parnell’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium,” which Port describes in The Birth of Loud as “the British equivalent of Ed Sullivan, but with even worse sound.” Watching the live telecast on the evening of March 2 were a couple of teenagers from Liverpool named John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who, Port writes, were “mesmerized by the curves of Buddy’s guitar.” The two were also impressed enough by Holly’s music and style that they changed the name of their incubating band from the Quarrymen to the Beetles, before changing it once more—Lennon, a pathological punster, thought the word “beat” was a better allusion to the music of the day than the name of a bug.

The Strat, therefore, was a guitar that the Peavey Electronics Corporation of Meridian, Mississippi, would have wanted to copy. But Leo Fender’s first guitar, the Esquire? Not so much. As Port describes it, when the Esquire was introduced in the summer of 1950 at the National Association of Music Merchants convention in Chicago, the instrument was derided by competitors as a “toilet seat with strings.” In fact, the Esquire did have a lot in common with crap. Early examples were plagued by shorts in the guitar’s single pickup, the microphone-like component made from a magnet tightly wrapped in copper wire.

When Leo Fender’s first solid-body electric guitar, the Esquire, was introduced in 1950, it was plagued by pickup problems and bowing necks. Those defects would be fixed in 1951 with the release of the similarly designed Telecaster. Photo via Gardiner Houlgate.

Electrical shorts would seem an unforgivable error for an electricity wizard like Leo Fender, but almost more problematic was the pickup’s hard, sharp sound, a tone that was fine for country pickers in honky-tonks but completely unsuited, Port writes, to the needs of the rhythm guitarists backing them up. The Esquire’s sound was also a very poor cousin to the warm, mellow tone of Gibson’s electric hollow-body workhorse, the Super 400. So, in 1950, with Fender selling Esquires even as customers were returning them to correct various defects, Leo Fender went back to the drawing board, rewiring the pickup and adding a second one that was shielded by a chrome-plated cover, which reduced the intensity of the high-frequency signals the pickup was capturing.

Then things got worse. “One day,” Port writes, “Leo Fender looked at his Esquire prototype and realized that its neck was bending upward, succumbing to pressure from the strings.” Fender’s head of marketing and sales, Don Randall, had warned Leo Fender that this was going to be a problem, but Fender apparently believed the maple he was using for the Esquire’s neck, which was bolted to the guitar’s ash body, would be strong enough to withstand the strain. It was not, and now production at the Fender factory ground to a halt as Leo Fender and a few of his most trusted employees struggled to solve this potentially company-killing problem.

One of those employees was George Fullerton, who had joined the company in 1948 and would work with Leo for 43 years, right until the great man died in 1991. At the time of the Esquire debacle, George’s father, Fred, was also working at Fender, and it was Fred Fullerton who figured how to cut a channel in the back of the Esquire’s maple neck, install a rigid steel truss rod, and then cover it up with a strip of walnut, all in a way that would allow the instrument to be mass-produced.

An early sales sheet for the Telecaster called out the “solo-lead pickup” hidden under a plate that also hid the bridge. The black bar in the top-right corner suggests that this sales sheet may have originally featured the model name “Broadcaster,” which Fender had to drop due to a lawsuit from Gretsch.

This redesigned, two-pickup guitar was renamed the Broadcaster, which immediately prompted a trademark-infringement lawsuit by Gretsch. But Fender had orders to fill—for Esquires, actually, but Leo wasn’t keen about letting too many more of those out into the world—so the company shipped about 60 guitars to customers with no model name on them at all. In the meantime, Don Randall had come up with the word Telecaster, which is why those Telecasters that were sold without a model name on them are known today as Nocasters. In the Telecaster, Fender had finally delivered the world’s first mass-produced solid-body electric guitar, which it sold for $189.50, plus $39.95 for a hardshell case (multiply those numbers by 10 for 2019 dollars).

Fender could not make Telecasters fast enough, and Randall wanted to keep his foot on the gas, lest Fender’s biggest potential competitor, Gibson, decided to make a solid-body of its own. What Fender needed, Randall reasoned, was a marquee endorsement, and in 1951, no electric guitarist was more marquee than Les Paul, who had just released one of the biggest hits of career.

At the time, Leo Fender and Les Paul were friendly, if not exactly friends. Like Leo, Les was an inveterate tinkerer, pioneering advances in multi-track recording when he wasn’t making his own pickups and electric guitars, which he called his clunkers. But unlike Leo, who never learned to play the instruments he made, Les could play the tar out of an electric guitar. Leo’s interest was essentially technical—solving one vexing problem after another was his joy, an end in and of itself. Les loved technology, too, but his goal was to create a guitar that would produce a loud, clean tone that no one else could duplicate, a sound that would be unmistakably “Les Paul.”

When western swing star Merle Travis asked his steel-guitar maker Paul Bigsby to build him a solid-body electric guitar, he was performing ditties like this.

To that end, Paul had built his own prototype in 1940, three years before Fender’s radio shop guitar. Paul’s guitar was a Frankenstein monster of an instrument. It featured a stock Epiphone guitar neck glued to a 2-foot length of 4-by-4-inch pine. After screwing a homemade pickup onto it and stringing it with strings, Paul dubbed his creation the Log.

“Unlike Leo Fender, Les Paul could play the tar out of an electric guitar.”

As described in The Birth of Loud, on the Sunday evening Paul finished the Log, he took it to a bar called Gladys’ near his home in Queens, New York. “He pulled his mutant guitar up on the small stage,” Port writes, “fired up his Gibson amplifier, and strummed a chord. The purely electric sound he’d so long dreamed of came splattering out of the little speaker. It was thin and sharp, prickly and alien. It possessed none of the mellow warmth, the woody grace, of a hollow-body electric—but it did have some of the qualities Les had dreamed of.” Those qualities included being able to crank his amp as loud as he wanted without worrying about feedback. As for the Log’s sound, “because its dense, solid-wood body didn’t absorb vibrations easily,” Port writes, “the strings themselves vibrated longer than on an acoustic instrument, giving each note a lyrical sustain.”

Two years later, in 1942, after electrocuting himself in his basement workshop, an accident that sidelined him as a guitarist for a spell, Paul took his Log to Gibson, with whom he already had an endorsement deal thanks to his status as a rising jazz guitarist. By now the Log had a more traditional body so that it looked more like a Spanish style electric guitar than a 4-by-4 with strings. Paul was sure Gibson would jump at the chance to be the first guitar manufacturer to release a solid-body electric guitar, but Gibson executives practically laughed him out of their offices, dismissing his Log as “a broomstick with pickups.”

The heart of Les Paul’s 1940 Log guitar, which is now at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, is an Epiphone neck and a 4-by-4. The Epiphone body parts were added later. Photo by Don Mitchell.

Undaunted, Paul moved to Hollywood in 1943 (the same year Muddy Waters left Mississippi for Chicago and that Leo Fender made his radio shop guitar) with the unusually specific goal of accompanying Bing Crosby on a song. Recording with Crosby, Paul thought, would boost his career. By 1945, Paul had insinuated himself enough into Crosby’s orbit that the two teamed up on a recording for Decca called “It’s Been a Long Long Time.” The song was a smash and, as he had hoped, Paul was soon the toast of the town.

Naturally, Paul continued to tinker, but instead of a cramped basement in Queens, he now had a comparatively spacious garage studio adjacent to his Hollywood bungalow. In fact, Paul’s bungalow and its legendary garage became a frequent hangout for LA’s best studio musicians, who called themselves the Hollywood Hillbillies when they played there with Paul. After a session, Paul and his buddies would amble over to the patio, pull up some chairs, and toss back a few cool ones in the shade of an orange tree.

When Les Paul arrived in Hollywood in 1943, his goal was to record a song with Bing Crosby. Paul achieved his goal in 1945 when he and Crosby teamed up on “It’s Been A Long Long Time,” which was Paul’s first hit.

In 1947, several of these soirees included Leo Fender, who one day brought along custom-steel-guitar maker Paul Bigsby as his plus-one. The three guitar gurus would get together regularly after that, nerding out for hours on end about pickup magnets and frequency equalization. Eventually, Bigsby brought Paul a new pickup to try out, which, Port writes, Paul liked so well, he tried to hide it from fellow guitarists such as Chet Atkins and Merle Travis. Both players were soon asking Bigsby for a pickup like the one he’d made for Paul, but Travis went further, requesting a complete guitar.

Bigsby delivered his new guitar to Merle Travis in the spring of 1948. Soon after, Fender got to see and hear the instrument for himself when Travis played it at a western dance concert one Saturday night at American Legion Post No. 277, just outside of Fullerton. “It was a standard guitar—the kind you fret with your fingers, not a steel—but like nothing Leo had ever seen,” Port writes. “Its body was impossibly, absurdly, beautifully thin: an inch and a half, perhaps, from the back to the front. This body had the same height and width as a standard acoustic, but with no thickness and no sound holes. Its top was all solid wood. Solid bird’s-eye maple, in fact, so the entire thing, its usual hourglass guitar-body shape, gleamed as if gilded, and appeared to be spotted with rivulets of darker wood: the so-called bird’s eyes in the maple. The accent pieces around the bridge were intricate, even florid. The headstock was a flowing, avian shape with all its tuners arranged on top, to be within easy reach of the player.”

Merle Travis holding his Bigsby guitar, which is easily identifiable thanks to its distinctive headstock. Photo via WMOT Roots Radio.

As fate would have it, that spring Fender was under pressure from his sales team to design a production-ready follow-up to his radio shop guitar of 1943. “Now he knew he had to do it—and soon,” Port continues in The Birth of Loud. “Travis’s Bigsby guitar was getting all kinds of attention: from onlookers who’d never seen such a skinny six-string, from players who’d never heard anything like the sweet electric patter it emitted through an amplifier. That Bigsby guitar was alluring—for Leo, dangerously so.”

Before Travis took the stage, Fender peppered him with questions about his new guitar. For his part, Travis was only too happy to brag about his new pride and joy, going so far as to loan it to Fender for a full week until his next gig the following Saturday. Fender, Port writes, “was dying to get the guitar back to his workbench, to run its signal through his oscilloscope.”

A fair amount of that Merle Travis Bigsby would eventually make its way into the Fender Esquire of 1950 and the Telecaster of 1951. In particular, Leo Fender copied a key feature of Paul Bigsby’s headstock design, in which all of the tuners were aligned on one side. But Bigsby was not the only guitar maker Fender found inspiring. The method of bolting the Esquire’s neck to its body, which would become a hallmark of Fender guitars in the coming decades, was actually lifted from a Southern California guitar manufacturer named Rickenbacker.

This sheet music for “How High the Moon”, Les Paul’s and Mary Ford’s smash hit of 1951, shows Paul cradling one of his hand-built clunker guitars.

Which is not to say that Leo Fender brought nothing of his own to the table. “From the maze of an electric circuit—from the countless possibilities of resistors and capacitors and potentiometers and magnets and wiring and power supplies and schematics—Leo Fender could conjure whatever lush and evocative sounds he desired,” Port writes. Indeed, Fender’s electrical intuition had always been his company’s secret sauce, more than offsetting Fender’s occasional pragmatic plagiarism when it came to manufacturing decisions involving mere nuts and bolts.

Beginning in the spring of 1951, shiny new Telecasters, with their reinforced necks and dual pickups, were shipping to retailers across the country as fast as the Fender factory in Fullerton could manufacture and assemble them. Which brings us back to the decision by Don Randall to approach Les Paul about endorsing the Fender Telecaster. At the time, Paul was basking in the glow of his biggest hit ever, “How High The Moon,” recorded a few months earlier with his second wife, the singer and guitarist Mary Ford.

At first, Paul seemed receptive to the idea of putting his name on his friend Leo’s guitar, but Paul wasn’t all that crazy about the Telecaster’s sound. Meanwhile, the Telecaster had finally convinced Gibson that it needed to manufacture a solid-body electric guitar—within a few months of Randall’s overture, Gibson, too, began talking to Les Paul.

Advertisements for the 1952 Les Paul bragged that Paul had designed his signature guitar, hoping it would boost sales. In fact, Gibson’s president, Ted McCarty, deserves the credit.

The guitar that Gibson began working on as its answer to the Telecaster would not look anything like Les Paul’s Log, which the company had declined to build back in 1942. Instead, Gibson wanted a solid-body electric that felt like it truly belonged to Gibson’s extended family of illustrious instruments. To that end, Gibson’s president, Ted McCarty, led the design team, which prototyped a stunning gold-topped solid-body electric guitar that was a Gibson through and through, from its rounded body to its traditionally glued neck—a Gibson guitar would never be bolted! It even featured a contoured maple veneer on the guitar’s top, which was rounded to allude to the curves of an old-fashioned archtop guitar. It was, in short, as far from the plank-of-wood utilitarianism of the Telecaster as possible. As for its tone, this new Gibson guitar sounded rich and warm, much better suited to a jazzman like Les Paul than the country-western pickers for whom the twangy Telecaster had been designed.

And so, in the fall of 1951, Gibson showed their new solid-body electric guitar to Les Paul, who, according to Port, had a difficult time containing his enthusiasm for the instrument. After an all-night negotiating session, which was “fueled by pots coffee that Mary brewed and poured,” Les Paul agreed to affix his signature to Ted McCarty’s guitar.

The 1952 Les Paul featured a gold top and a trapeze bridge. Photo via Garret Park Guitars.

In 1952, Gibson’s new Les Paul Model, which weighed a whopping 9 pounds, hit the market. For Fender, the one-two punch of the Gibson and Les Paul names on the same instrument was nothing less than an existential threat, a product that could put the upstart Southern California company out of business in a New York minute. There was no time to rest on the laurels they’d earned with the Telecaster, so Leo Fender and his trusted colleague George Fullerton got to work on a new solid-body electric guitar that would address some of the complaints about the Telecaster, and hopefully leave Gibson’s Les Paul Model in the dust.

To accomplish this feat, Leo Fender would once again pillage from Paul Bigsby. Fender had already borrowed Bigsby’s headstock design, in which all the tuners were on the same side, but Bigsby wasn’t especially bothered by that. That’s because for Bigsby, the Telecaster represented a new market for his new True Vibrato units, which were introduced the same year as Gibson’s Les Paul.

A Bigsby B7 True Vibrato on a Gibson ES-330. The B7 was the first whammy bar. Photo via Bigsby.

The Bigsby True Vibrato was basically a customized guitar bridge, which is the piece of hardware that secures the strings to the bottom end of a guitar’s body. When the whammy bar, as it came to be called, on the Bigsby vibrato was depressed, guitarists could change the pitch of whatever chord or note they were playing, causing their instruments to moan like a locomotive whistle or “boing” like a spring.

Best of all for Bigsby, vibrato units could be mass-produced, making them a less labor-intensive revenue stream than his guitars, which were custom-built one at a time. Bigsby had already tooled up machinery to manufacture vibratos in dimensions designed to fit Gibson and Gretsch guitars. In 1953, he released a vibrato unit designed to augment the standard bridge that came with a Telecaster, too.

Don Randall, smarting, perhaps, from his failure to land Les Paul, did not appreciate another company making money off of Fender’s most popular product, so when Leo Fender and George Fullerton set out to build the guitar that would become the Stratocaster, which made it to market in October of 1954, the mandate was that it have its own proprietary Fender whammy bar.

Advertisements for the Fender Stratocaster touted its “Tremolo Action,” which was a feature lifted from Paul Bigsby, from whom Fender also copied the Strat’s headstock.

In The Birth of Loud, Ian Port shares Bigsby’s succinct reaction to seeing a brochure for the Stratocaster for the first time: “That son of a bitch ripped me off!” In part, Bigsby was angry that Fender customers who wanted what Fender was calling “tremolo action” were being steered to Fender’s new Stratocaster, obviating the need to purchase a “nifty add-on” from Bigsby. But even worse was the Strat’s headstock. Like Bigsby’s Merle Travis guitar, the tuners were all on one side, but the top of the Telecaster’s headstock had ended in an inelegant stub. Not so the Stratocaster, which copied the round knob that had been a defining feature of Bigsby guitars since 1948. “For the rest of his life,” Port writes, “Leo Fender would deny copying Bigsby. But, though he may have seen an older instrument in a museum at some point, he’d clearly borrowed another one of Bigsby’s designs.”

In the end, it was the Stratocaster that killed the Gibson Les Paul Model rather than the other way around. It had a trio of pickups over the Les Paul’s pair, and was fully 2 pounds lighter, which made Stratocasters easier to carry over the course of a long night onstage. The Strat was also contoured to fit a player’s body, thanks to input from a country picker, and part-time Fender employee, named Bill Carson, who took a hacksaw to his Telecaster where the guitar’s body cut into his chest and forearm. This addressed one of the main complaints about the Telecaster, that it was physically uncomfortable to play. Carson also made hacksaw adjustments to the bridge, which improved the guitar’s tuning, making it an instrument that pros in a recording studio could count on to keep them pitch perfect.

In short, the Stratocaster was a better instrument than the Telecaster, although that’s not why John Lennon and Paul McCartney were so excited when they saw Buddy Holly play one on live television in 1958. The curvaceous Strat was also sexy, in a way the handsome, tasteful Les Paul would never be.

It may not look like much, but the photo at top right of Eric Clapton tuning his 1960 Les Paul—it was published on the back cover of a 1966 John Mayall album—created so much demand for the discontinued guitar that Gibson brought it back in 1968. Photo via Sound Station.

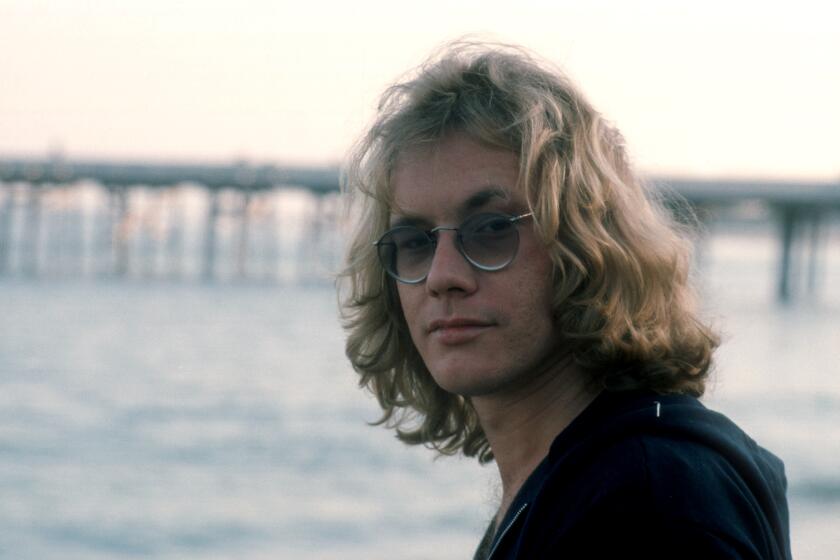

Still, the Les Paul Model’s death would prove temporary, lasting from 1961, when Gibson stopped making the slow-selling, heavy instruments, until 1968, when the company reintroduced two new lines of Les Paul guitars. The catalyst had been the renewed interest in vintage Les Paul Model guitars that had exploded in 1966, after a photograph of Eric Clapton holding his 1960 Les Paul made the back cover of a trendsetting John Mayall album called “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton.” But the Les Paul would never be a threat to the Strat, in no small part because by 1968, another guitarist had aligned himself with Stratocasters, which he played upside-down, restrung because he was left-handed, and occasionally set on fire during performances. That guitarist was Jimi Hendrix.

One of the most iconic moments of the Monterey Pop Festival of 1967 was when Jimi Hendrix set fire to one of his Stratocasters live onstage. Photo via Amazon.

In a way, musicians like Hendrix and Clapton, who would appear on many of his own subsequent album covers playing a Stratocaster, were proxies in this battle between the two landmark instruments of rock ‘n’ roll, and, by extension, Leo Fender and Les Paul. Similarly, Ian Port and every other guitarist who has imagined themself onstage, a guitar strapped to their neck as the multitudes showered them with waves of adulation, have been proxies, too, even if their instruments were Peavey Predators and their guitar heroes were artists like Kurt Cobain of Nirvana. His band’s so-called grunge-rock sound had followed punk, which had been an emphatic middle finger to the arena rock of the 1970s, which had embraced the power chords of ’60s rock but none of the psychedelia. Naturally, Cobain and the other guitarists who fronted these bands in the decades after the Telecaster, Les Paul, and Stratocaster first came on the scene played all sorts of electric guitars. But in proclaiming their independence from the Stratocaster and Les Paul in particular, they reminded us that these two guitars, initially created for a country picker and a jazz guitarist, remained the standards by which everything since is still measured.

The Birth of Loud, by Ian Port, is published by Scribner.